In the pursuit of elite athletic performance, the focus often narrows to a single hormone: testosterone. Athletes and coaches frequently look for ways to maximize "free" testosterone—the bioavailable fraction of the hormone that is not bound to proteins and can freely interact with androgen receptors to drive muscle protein synthesis, bone density, and recovery.

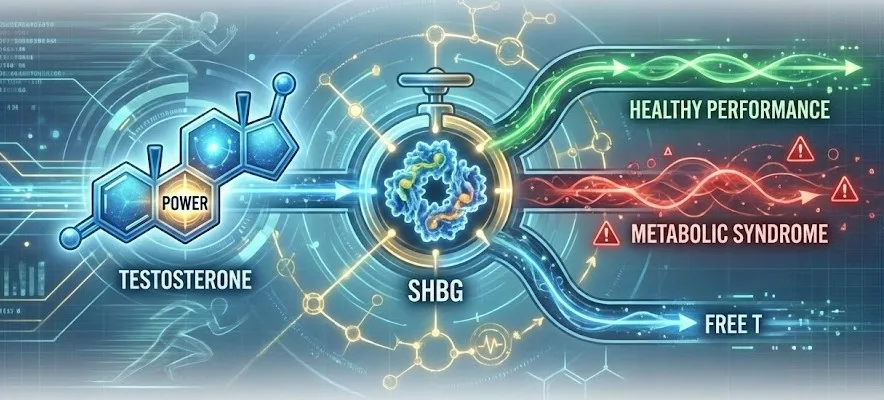

However, this narrow focus often overlooks the crucial role of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). Produced primarily in the liver, SHBG is far more than a passive transport protein; it is the physiological gatekeeper that regulates the body's hormonal environment. While many athletes attempt to suppress SHBG to unlock more free testosterone, doing so beyond natural physiological limits can trigger a cascade of metabolic complications.

The Free Hormone Hypothesis and Bioavailability

In the bloodstream, testosterone exists in three primary states:

-

SHBG-Bound (approx. 60–70%): Testosterone is tightly bound to SHBG and is biologically inactive.

-

Albumin-Bound (approx. 30–40%): Testosterone is weakly bound to albumin and can become available relatively easily.

-

Free Testosterone (approx. 1–2%): The truly "unbound" and active portion.

According to the Free Hormone Hypothesis, it is the free fraction that largely determines the androgenic effect on the body. This has led to a trend in sports science where athletes monitor SHBG levels closely, aiming for the lower end of the reference range to ensure their "Total Testosterone" isn't being "wasted" by binding proteins.

Why "Lower" Isn't Always "Better"

While high SHBG can indeed limit performance by sequestering too much testosterone—often seen in cases of overtraining or extreme calorie restriction—the opposite extreme is equally detrimental. SHBG is a highly sensitive metabolic biomarker.

When SHBG levels drop below the physiological floor, it is rarely an isolated event. Low SHBG is clinically recognized as a primary marker for Metabolic Syndrome. This cluster of conditions includes:

-

Insulin Resistance: High circulating insulin levels actively suppress SHBG production in the liver.

-

Systemic Inflammation: Pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha can downregulate the SHBG gene.

-

Hepatic Steatosis (Fatty Liver): Low SHBG is strongly correlated with the accumulation of fat in the liver, even in seemingly "fit" athletes who may be over-consuming processed sugars or utilizing performance-enhancing substances.

The Athlete’s Paradox: Performance vs. Health

For an athlete, the irony of crushing SHBG is that the very metabolic issues it signals—insulin resistance and inflammation—are the ultimate enemies of performance.

-

Muscle Growth vs. Insulin Sensitivity: If SHBG is low because of insulin resistance, the body's ability to shuttle nutrients into muscle cells is impaired.

-

Recovery and Inflammation: Systemic inflammation signaled by low SHBG slows down tissue repair and increases the risk of injury.

-

The PED Factor: The use of anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) drastically reduces SHBG. While this temporarily increases free hormone levels, it creates a "metabolic vacuum" that can lead to rapid lipid profile deterioration and cardiovascular strain.

Maintaining the Hormonal "Goldilocks Zone"

A truly optimized athlete does not aim for the lowest possible SHBG, but rather a level that reflects metabolic flexibility.

| Factor | Effect on SHBG | Impact on Athlete |

| High-Fiber/Moderate Carb Diet | Tends to Increase/Stabilize | Supports liver health and steady energy. |

| Excessive Simple Sugars | Decreases | Triggers insulin spikes that suppress SHBG. |

| Overtraining/Low Energy Availability | Increases | Signals the body to "hibernate" by sequestering T. |

| Healthy Body Composition | Optimizes | Minimizes inflammation and maintains SHBG sensitivity. |

Conclusion

The goal for any athlete should be homeostasis, not just maximization. SHBG serves as a vital "check engine light" for the human body. When it is within a normal physiological range, it ensures that testosterone is delivered steadily and that the metabolic machinery—the liver, the pancreas, and the vascular system—is functioning correctly. Pursuing free testosterone at the expense of SHBG is a short-term strategy that often leads to long-term metabolic decline.