The image of an athlete pushing past their limit is iconic in sports—the grimace of effort, the straining muscles, the final kick toward the finish line. Yet, what determines success in those critical moments is not just mental fortitude or visible musculature. It is a complex, microscopic series of chemical reactions happening deep within the cells.

For decades, a gap has existed between practical coaching ("bro-science") and rigorous sports physiology. Bridging this gap means understanding that the body’s energy systems are not abstract concepts, but tangible biological pathways that can be trained, fueled, and manipulated. The cornerstone of this understanding lies in how the body processes sugar under duress: the relationship between glycolysis, lactate, and recovery.

The Engine Room: Glycolysis and Sudden Energy

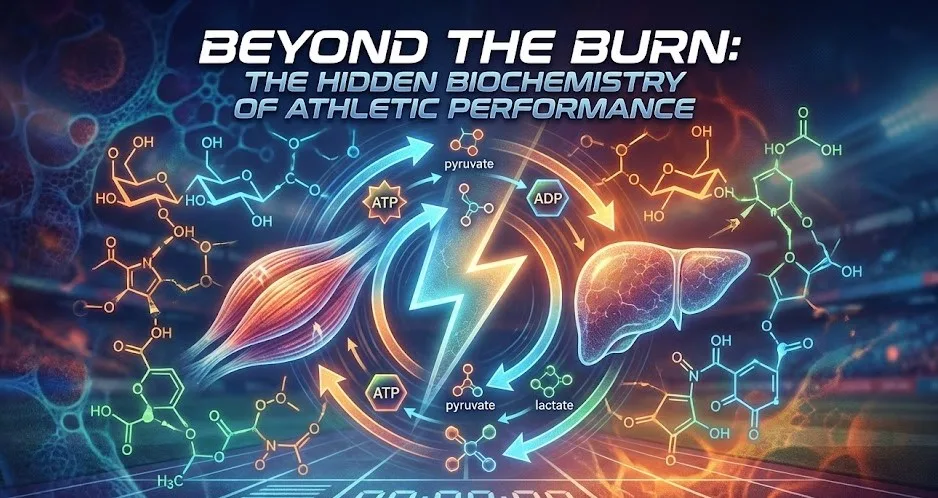

Every muscle contraction requires adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the body's universal energy currency. During explosive movements or intense exercise, the demand for ATP skyrockets faster than oxygen can be delivered to the tissues. To meet this immediate demand, the body turns to its stored fuel reserves: glycogen.

Glycogen, stored in the muscles and liver, is broken down into glucose units. Through a process called glycolysis, this glucose is rapidly fractured to produce ATP. This pathway is fast, essential for high-intensity work, but it has a metabolic cost. The end product of normal glycolysis is pyruvate. When oxygen is plentiful, pyruvate enters the mitochondria to create massive amounts of energy efficiently.

However, during peak athletic exertion, the "oxygen window" closes. The mitochondria cannot accept the pyruvate fast enough.

The Lactate Misconception

When the aerobic pathway is backed up due to intensity, the body faces a crisis. Glycolysis requires specific carrier molecules (NAD+) to keep running. If these molecules are all used up, energy production stops, and the athlete hits a wall.

To prevent this cellular stall, the body activates an evolutionary fail-safe. An enzyme known as Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) converts the excess pyruvate into lactate.

For years, lactate (often confused with lactic acid) was vilified as a waste product responsible for muscle soreness and fatigue. Modern sports science recognizes this as a gross misconception. The conversion to lactate is not a mistake; it is a vital survival mechanism. By creating lactate, the body regenerates the necessary carrier molecules (NAD+) to allow glycolysis to continue.

Lactate is not the enemy stopping the athlete; it is the temporary solution allowing them to sprint for those extra thirty seconds.

The Recycling Plant: The Cori Cycle

The story of energy does not end with lactate production in the muscle. The human body is incredibly thrifty. The lactate produced during intense exercise is a valuable fuel source waiting to be reclaimed.

Lactate leaks out of the working muscle cells into the bloodstream, where it can be utilized by the heart and brain for fuel. Crucially, much of it travels to the liver. The liver performs a remarkable metabolic feat known as the Cori Cycle. It takes the "waste" lactate and, using energy, converts it back into glucose. This new glucose is then released back into the bloodstream to be used by the muscles again or stored as glycogen for future efforts.

This cycle highlights a critical aspect of endurance: the ability to clear and recycle lactate is just as important as the ability to produce energy quickly.

From Biochemistry to the Podium

Why does a coach or an athlete need to understand cellular respiration? Because elite training methodologies are built upon these biological realities.

Understanding these pathways informs everything from nutrition to doping protocols. For instance, knowing the specifics of carbohydrate metabolism dictates the precise timing and type of sugary drinks an endurance athlete consumes to maintain glycolytic flux without causing gastrointestinal distress.

Furthermore, deeper knowledge allows for smarter training. "Lactate threshold" training is essentially teaching the body to become more efficient at the Cori Cycle—clearing lactate faster than it is produced. Similarly, hypoxia training (training in low-oxygen environments) forces the body to optimize these anaerobic pathways, making the enzymes involved, like LDH, more efficient.

In the realm of sports medicine and anti-doping, these markers become tell-tale signs. Elevated levels of certain enzymes, including specific forms of LDH, can indicate tissue damage from overtraining or, in some contexts, be red flags for the use of performance-enhancing substances that alter metabolic rates.

Conclusion

Athletic performance is ultimately a macroscopic expression of microscopic efficiency. While grit and determination drive the athlete, the biochemical machinery sets the speed limit. By respecting the complex dance of glucose, lactate, and the liver's recycling capabilities, coaches and athletes move beyond guesswork, turning physiological constraints into competitive advantages.