For athletes and fitness enthusiasts, protein is often lauded as the cornerstone of muscle growth and recovery. While consuming adequate protein is undoubtedly crucial, understanding how the body processes and utilizes this vital macronutrient is key to optimizing performance and achieving desired results. The journey of protein from your plate to your muscles is a complex one, with significant implications for athletic nutrition.

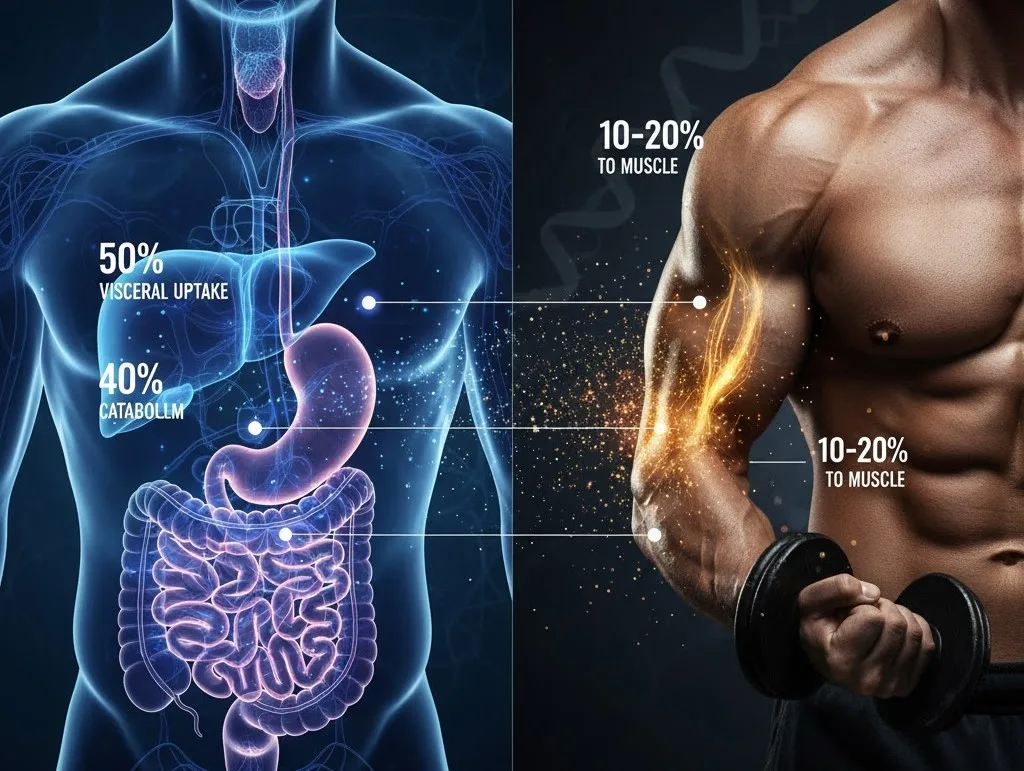

When an athlete consumes protein, whether from a shake or a meal, it doesn't immediately become muscle tissue. Instead, it embarks on an intricate pathway. A substantial portion, roughly 50% of ingested protein, is first taken up by visceral organs, primarily the gut and the liver. These organs are highly metabolic and have significant protein demands of their own. The gut requires protein for its structural integrity, enzyme production, and nutrient transport, while the liver uses it for a myriad of metabolic processes, including the synthesis of various proteins, hormones, and detoxification. This initial "siphon" by the visceral tissues means that a large part of the protein you consume is prioritized for these vital bodily functions before it even has a chance to enter the general circulation.

Beyond this initial uptake, a further portion of the ingested protein, about 40%, is catabolized – broken down for energy. This process helps fuel various metabolic activities, including the synthesis of urea (a waste product) and neurotransmitters. While essential for overall bodily function, this also means that a significant amount of protein isn't directly contributing to muscle repair or growth.

Furthermore, a smaller percentage, around 11%, is directed towards de novo protein synthesis, meaning the creation of new proteins throughout the body, not exclusively muscle protein. This constant turnover is necessary for maintaining healthy tissues and cellular function.

The critical takeaway for athletes is the relatively small percentage that ultimately reaches the muscles for repair and growth. After the gut, liver, and other visceral tissues have taken their share, and some protein has been used for energy or general synthesis, only an estimated 10-20% of the ingested protein finally makes its way to the muscle tissue.

This biological reality underscores the importance of several nutritional strategies for athletes:

-

Protein Timing: While the "anabolic window" might not be as narrow as once thought, consuming protein strategically around training sessions can help ensure a steady supply when muscle protein synthesis is most elevated.

-

Protein Quality: The type of protein matters. Proteins rich in essential amino acids, particularly leucine, are more effective at stimulating muscle protein synthesis. Dairy proteins like whey are renowned for their high biological value and rapid absorption.

-

Adequate Intake: Given that a significant portion of ingested protein is utilized elsewhere, athletes often require higher overall protein intakes than sedentary individuals to ensure sufficient amounts reach the muscles for optimal recovery and adaptation.

-

Gut Health: A healthy gut is crucial for efficient protein digestion and absorption. Issues with gut health can compromise the initial breakdown and uptake of protein, further reducing the amount available for muscle.

Understanding the fate of ingested protein helps athletes move beyond simply consuming high amounts and encourages a more nuanced approach to nutrition. It highlights the body's complex prioritization of protein for overall health and function, and why optimizing protein intake through quality, timing, and quantity is paramount for athletic success.