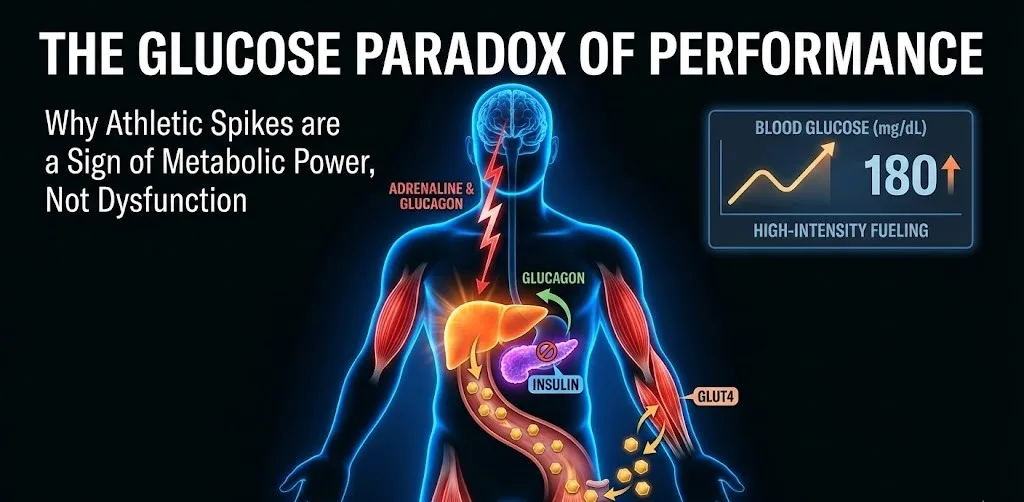

In the traditional understanding of metabolic health, high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) is often viewed through the lens of pathology—a red flag for insulin resistance or pancreatic dysfunction. However, for elite athletes and high-intensity trainees, a significant rise in blood glucose during exercise is not a sign of failure but a hallmark of a finely tuned physiological system. This phenomenon, often referred to as exercise-induced hyperglycemia, represents a deliberate "fueling strategy" orchestrated by the endocrine system to meet the extreme demands of peak performance.

The Hormonal Symphony of High Intensity

When an athlete shifts from a steady state into high-intensity interval training (HIIT), sprinting, or heavy resistance lifting, the body perceives a massive demand for immediate energy. The central nervous system triggers the sympathetic "fight or flight" response, resulting in a surge of catecholamines—specifically epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine.

These hormones serve as the primary conductors of the metabolic orchestra. Their first task is to signal the alpha cells in the pancreas to secrete glucagon while simultaneously exerting a powerful inhibitory effect on the beta cells.

The Pancreas: A Strategic "Off Switch"

One might assume that rising blood sugar should naturally trigger the release of insulin to bring levels down. However, during intense sport, the body employs a protective mechanism called alpha-adrenergic inhibition. Adrenaline binds to alpha-2 receptors on the pancreatic beta cells, effectively "switching off" insulin secretion.

This suppression is critical for two reasons:

-

Energy Availability: If insulin were to rise alongside blood sugar, it would drive glucose into fat cells and the liver for storage, effectively "robbing" the working muscles of their fuel.

-

Prevention of Hypoglycemia: Exercise increases the muscles' sensitivity to insulin. If insulin levels remained high during intense exertion, blood sugar would plummet too rapidly, leading to a "bonk" or metabolic crash that could be dangerous mid-competition.

The Liver as a High-Pressure Fuel Pump

While the pancreas stays quiet, the liver goes into overdrive. Stimulated by glucagon and adrenaline, the liver accelerates two key processes:

-

Glycogenolysis: The rapid breakdown of stored glycogen into glucose.

-

Gluconeogenesis: The creation of new glucose from non-carbohydrate sources like lactate and glycerol.

In high-intensity efforts, the rate of hepatic glucose production (the speed at which the liver pumps sugar into the blood) can exceed the rate of glucose uptake by the muscles by a factor of seven or eight. This creates a temporary "overflow" in the bloodstream, resulting in the high glucose readings often seen on Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs) worn by athletes.

The GLUT4 Mechanism: Insulin-Independent Uptake

A common question among sports scientists is how muscles continue to take up glucose if insulin is suppressed. The answer lies in GLUT4 translocation. Skeletal muscle contractions trigger the movement of GLUT4 glucose transporters to the cell membrane through insulin-independent pathways (such as AMPK activation). This allows athletes to fuel their muscles effectively even when their pancreatic insulin output is at a baseline minimum.

Distinguishing Adaptation from Dysfunction

It is vital to differentiate this athletic spike from the hyperglycemia seen in sedentary individuals. In a non-athlete, high blood sugar is often the result of the body’s inability to move glucose out of the blood. In the athlete, it is the result of a highly efficient body moving glucose into the blood to ensure the brain and muscles never run out of "high-octane" fuel during a crisis.

Furthermore, these transient spikes are actually beneficial for long-term health. The metabolic stress of high-intensity exercise improves mitochondrial density and enhances post-exercise insulin sensitivity. Within 30 to 90 minutes after the workout ends, as adrenaline fades and the "off switch" on the pancreas is released, blood sugar typically returns to normal or even slightly below baseline as the muscles soak up the remaining glucose to replenish their internal stores.

Key Takeaways for Athletes

-

Context is King: A blood sugar reading of 180 mg/dL during a sprint is a sign of a robust stress response, not a metabolic disorder.

-

The Post-Exercise Window: The rapid decline in glucose after training is a primary indicator of metabolic flexibility.

-

Intensity Matters: Low-intensity "Zone 2" training typically results in stable or slightly declining glucose, as the body relies more on fat oxidation and maintains a tighter balance between glucose production and use.